An Iteration

Computer Games Design:

Introduction to Critical Games Design

“The Royal Game of Ur” is one of the first board games ever discovered and studying it at a full time course in university actually requires an understanding of it’s mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics, history and purpose. The iterations made on this game and presented in this paper are based on this process of understanding the game.

“The Royal Game of Ur” has been discovered 86 years ago, during the excavations of the graves in the Royal Cemetery in Ur ( located in nowadays Iraq British Museum

As for the rules of the game, they have stayed a mystery until, in 1956, a tablet discovered in 1880, was mentioned in a journal article about fortune telling. At the same time, in the same issue, another article featuring a slightly older tablet, but with very similar content, was written. (Finkel) Ervin Finkle notes in “Ancient Board Games in perspective” that the writings on the tablet are actually related to the “Royal Game of Ur”, representing a standard set of rules. Until this discovery, several types of gameplay have been suggested, of which some can be found in Finkel’s rendition of the rules.

I early talked about the mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics of the game. I observed this during the first playtest of the game. Me and my test partner played both variations of the game to get a better understanding. The playtest was based on the both variations of the game and the rules written in Ervin Finkel’s book:

- each player starts with 7 token

- each player starts on opposite sides of the play board

- players decide which of them starts first, on arbitrary methods

- the player who starts rolls 4 d4 dice, each tipped on 2 tips with a distinctive method (i.e. 2 of the tips are coated with Tipex, 2 are not)

- the player moves a single token as many squares as tipped dice he rolled. If he rolled no tipped dice, then he loses his turn

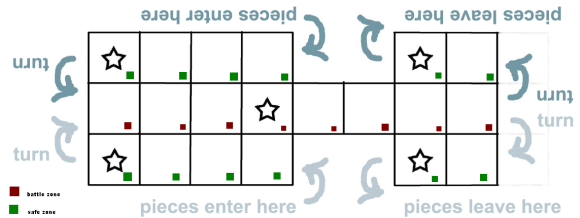

- if a player’s token lands on a “rosette” square (marked with stars in the illustration), he gets another turn

- the purpose of each player is to get all his tokens out of the board, following the movement in the illustrations

- a token on a “rosette” square is considered “safe” and cannot be “captured”

This rules, along with the type boards, are part of the game mechanics. Generally, game mechanics, consist of the rules of the game and the initial layout of the game.

“The Game of 20 Spaces”, the first iteration of the game of Ur.

The dynamics of the game are a direct result of the player’s interactions with the rules. In the case of “The Royal Game of Ur” they are represented by the racing component of the game, the capturing of the “rosette squares” and holding them as a strategic advantage.

The aesthetics emerge from playing the game and are the actual emotions the player has in relation with the game. Different mechanics and dynamics can lead to certain types of aesthetics, like annoyance or glee.

We play tested both game boards, using Finkel’s set of rules, but got to the conclusion that the iterated board was more interesting to play due to the increased challenge it proved. The initial board had more “safe zones” but the tactical options were limited due to the fact that the players had more opportunities to stay out of the “battle zone”.On the second board, the reduced number of “safe zones” and making the middle section longer offered a greater incentive for the players to race to the finish and gain control over the “rosette squares”. The iterations that we’ve done upon the game were done on “The Game of 20 Squares” board.

During the “Introduction to Critical Games Studies” we iterated “The Royal Game of Ur” as an exercise to better understand the game mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics and to try and adapt the game to the modern days.

The first iteration of the game was made taking into consideration that sometimes one of the players got stuck in the game by not being able to make any legal moves. When one gets into this situation his opponent would win the game. This iteration offers a reward to the player that manages to force the other player into a “no escape” situation. Also this iteration proved to be useful in turning a very long game in which a player may lose interest, into a shorter game, in which strategy may prove to be more useful to the gameplay development than just being patient.

Another way in which we thought of changing the game, and maybe speeding it up was the way the dice casts were read. Instead of using Tipex, which was then counted and based on the count, the number of square on which you could make a move was determined, it was decided to go with and even or odd numbers. The even numbers were taken into consideration when making a move, while the odd numbers weren’t. This really sped up the game, as the chances to roll at least one even number were greater than rolling a die with a painted tip, which would eventually be erased.

As a third iteration we decided to take inspiration from another game that has survived through the ages, Backgammon. As it was stated in Finkel’s paper, two pieces cannot share the same space, so one of the players is required to either jump over the opponents piece or decide upon another move. So with this new iteration when one player lands on an occupied space he takes out the other player and occupies that place for himself. To get back in the game the player has to roll a precise number. It was first decided that the player was supposed to roll 4 even numbers to get back in the game. Then, because the roll was quite difficult, we decided to keep it to a 2 even number roll. This iteration, along with the first one, made the dice rolls more valuable, giving them a true strategic function. We valued our moves more after these iterations took place, knowing that we could hinder our opponent with just one moment and thus gaining an advantage in the game. This iteration helped bring a new positive feedback loop, besides the one offered by the “rosette squares” by making the player to believe he has a slight advantage over the opponent.

The last iteration is derived again from an ancient game mechanic, “Alea Evangeli”. Firstly we decided to play the game as it was in the beginning, putting the other iterations aside. The new iteration was meant to change the core mechanic of the game from a racing game to a war game. And so the main goal of the game was not to get all your pieces to the finish faster, but capture as many of the enemies as you can along the way. This would seem hindering for a racing game, because the opponent, even with less pieces, would easier win, in a racing game. All of the captured pieces will come under your usage and with them capturing even more pieces and winning by taking all of your opponent’s pieces. This would seem hindering for a racing game, because the opponent, even with less pieces, would easier win, in a racing game. The mechanic adopted from “Alea Evangeli” consisted by capturing an opponent’s piece between two of your pieces. This iteration needed to be altered after a playtest because the game could go on for quite a while before a winner is determined. A limit of turns was added to keep the players interested in the game. Each player has 10 turns in which he had to capture as much of the opponent’s pieces as possible.

My playtest partner, decided that to this variation of the game, to keep the racing mechanic as well and when a player managed to get a piece of the board, he’s able to get that piece back in the game and also score two points, or “frags” as my playtest partner decided to name them. I considered this to be too much of a positive feedback loop to the game and offer too much of an advantage to a player.

Here I’ll keep my point of view and believe that giving up the race component of the game with this iteration and adding a slight change to the last “rosette square” making it a turning point and bringing players back on the table. This way players are confined to the board and the only pieces that are to leave the board are the captured ones. If a player has available legal moves after a die cast, then he can introduce the newly captured piece in the game. Eventually the board would get filled, so players have to keep to as many strategy based moves as possible to clear the board in ones favour.

The iterations made for this game either proved benefit to the game, or made the game too tedious. To follow up on what I picked up from the paper “MDA – A Formal Approach to Games Design”: When looking at a game from a designer’s point of view the first that had to be affected were the mechanics, this way changing the emergent dynamics and then the aesthetics. But when the iterations were approached from a players point of view, the aesthetics emergent from the game were the first to be observed, then the dynamics and finally the mechanics. The rules of the game put together by Finkle can be used to play all the iterations, and any changes have also been included in the iteration description.

As a final conclusion, making an 4000 year old game fit for this time requires iterations that impose a fast-paced and challenging gameplay, otherwise, most players might just loose interest if the game is not in a way related with this “speed era”.